Multi-Agent Systems: Implementation Best Practices

Over the last two years, developers have significantly changed how they use large language models.

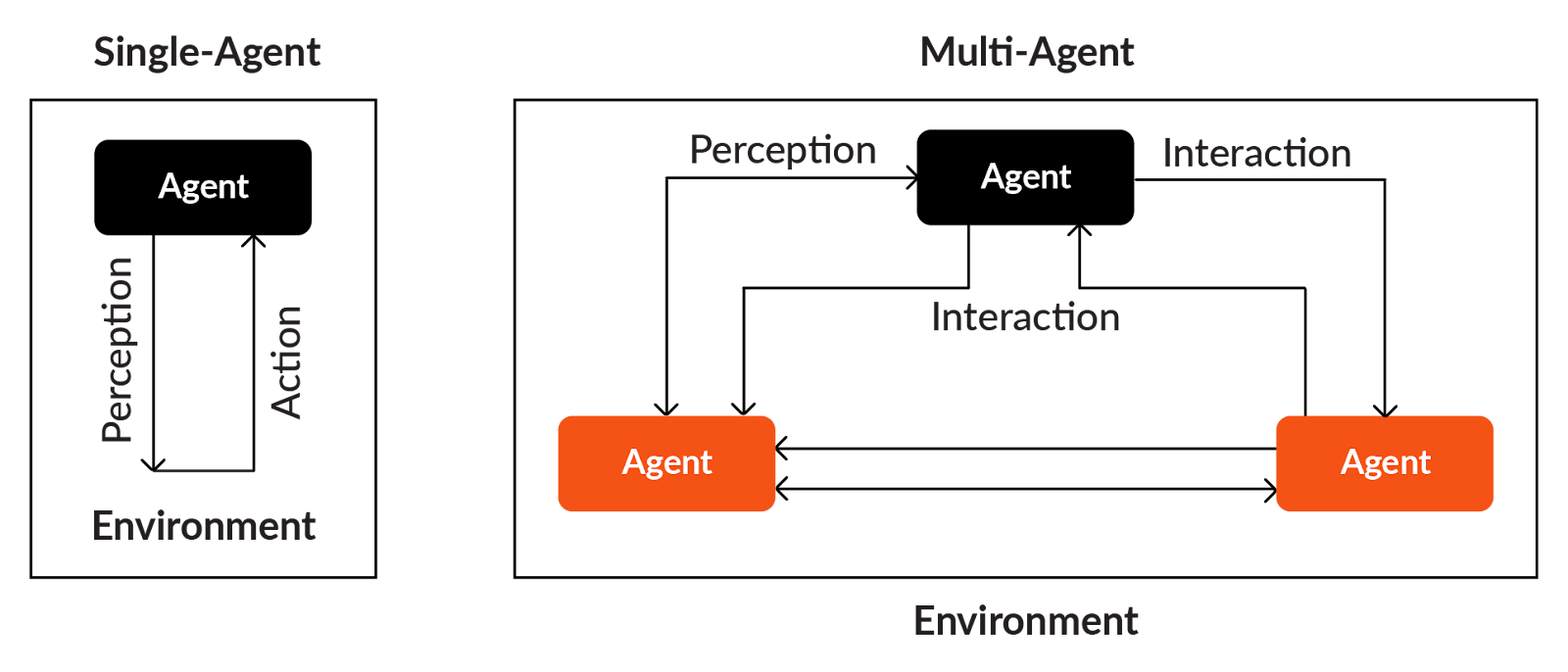

Initially, they interacted with LLMs through simple API calls, asking the model to generate text or answer a question. This approach worked well for small and direct tasks. Building on this, the next step was to create a single agent around the LLM API. This agent acted like a structured wrapper that handled reasoning steps, tool calls, memory, and actions. It could solve more complex tasks than a plain API call.

However, as real-world applications grow more complex, developers face workflows with multiple tasks, branching decisions, validations, and tool interactions. A single agent often struggles with this level of complexity. It has to think, plan, execute, verify results, and manage every part of the process. It made the system slow, difficult to maintain, and prone to errors.

Multi-agent systems address these challenges by having several autonomous agents work together in a shared environment. Each agent has a specialised role, and they coordinate through messages and shared context.

Research on LLM-based agent frameworks shows that this approach offers better modularity, easier scaling, and more reliable behaviour.

This article explores what a multi-agent system is, how it works, and how it can be designed for practical use.

Summary of key multi-agent system concepts

| Concept | Description |

|---|---|

| Multi-agent system components | A multi-agent setup contains: • Individual agents that can observe information, make decisions, and take actions. • Shared environment that provides data, tools, or constraints. • Interactions where agents exchange information, coordinate steps, and update the environment |

| Multi-agent communication | Agents communicate using structured message formats and protocols. • FIPA-ACL provides fields like performative, sender, receiver, and content that define the meaning of a message. • JSON or YAML payloads |

| Multi-agent coordination | Help agents decide which agent handles which task and how work is passed along. Examples include: • Auctions • Contract-net protocol • Voting • Negotiation |

| Multi-agent architectures | Agents can be organised in different layouts. • Centralized: One agent acts as a coordinator • Decentralized: Agents work peer to peer. Hierarchical or holonic: Agents work in layers or nested groups. • Coalition-based: Agents form temporary teams based on the task. Each structure offers different trade-offs in control, fault handling, communication load, and scalability. |

| Workflows & orchestration frameworks | Define how agents cooperate across multiple steps, managing task sequences, parallel flows, hand-offs, retries, memory, and logging. Examples include: • LangGraph • CrewAI • No-code platforms such as FME Developers can use them to set up agent roles, connect tools, and build repeatable workflows that can run reliably in production. |

| Multi-agent system challenges | • Communication overheads • Coordination complexity • Unexpected behaviour during agent interaction • Debugging difficulty • Escalating costs |

| Multi-agent system best practices | • Define roles clearly • Standardise message formats • Log every interaction • Add fallbacks • Control costs • Scale the number of agents gradually after testing |

Introduction to multi-agent systems (MAS)

A multi-agent setup is a way of organising several autonomous agents to work together on a task or workflow.

Single agent workflow

A single-agent workflow uses one agent to handle the entire task from beginning to end. This agent receives input, decides what to do, calls tools as needed, tracks intermediate information, and produces the final output. This style works well when the task is small, linear, and does not involve too many branching decisions or tool interactions.

However, as soon as the workflow becomes complex, a single-agent design begins to show limitations. The agent must manage several tasks at once, including interpreting input, planning, selecting multiple tools such as database calls and functions, handling failures, and executing follow-up steps. At some point, the quantum of logical workload executed by a single agent becomes too high for systematic debugging and observability.

Single agents also suffer from context window limits and the lost-in-the-middle phenomenon, which can cause hallucinations as context increases.

Multi-agent workflows

Each agent is an autonomous AI software unit capable of making decisions and performing actions.

Instead of a single agent handling everything from start to finish, MAS breaks the work into smaller responsibilities that different agents can manage more efficiently.

For example, one agent may analyse the user request, another may plan the sequence of actions, a third may talk to external APIs or tools, and another may check the results or evaluate errors.

Here are the main reasons why multi-agent setups are useful:

- Work is easier to organise and manage as long workflows can be split into stages

- Debugging becomes more straightforward as each agent is responsible for a specific step

- Workflows scale better as parallel steps can be scaled by adding more agents for a process-heavy stage.

- Easy to extend over time as new checks, validations, or steps can introduce a new agent over system re-design

- Failures are easier to handle as workflows can be retried or switched to alternative agents

- Better fit for complex tasks involving multiple decisions, tool calls, and validations

Core elements of a multi-agent system

A multi-agent setup is built on three fundamental building blocks:

Agents

An agent is an independent software unit that can read information, make decisions, and perform actions. Each agent has a defined role, its own instructions, and a set of capabilities such as accessing tools, retrieving data, or applying reasoning steps.

In a practical setup, an agent can be configured with:

- A specific goal (e.g., “extract key fields,” “plan next steps,” “validate results”)

- Its own rules or instructions describing what it should do

- Access to tools such as APIs, retrieval functions, or scripts

- Local memory to store short-term information required for its task

An agent is responsible for performing just one part well and depends on other functions and external API calls, which keeps the whole design modular and easy to maintain.

Environment

The environment is the shared workspace where all agents operate. It contains the information, tools, and resources that agents read from or interact with.

Depending on the workflow, the environment may include:

- Data sources (documents, APIs, databases)

- Retrieval systems (vector search, indexers)

- Tools and functions (calculation tools, extractors, external APIs)

- Task context (intermediate steps, shared memory, history)

- Constraints and rules (limits, validations, permissions)

Agents in the environment can observe the intermediate steps, act on them, update common information, and read what other agents have contributed.

Interaction

Interaction defines how agents communicate, coordinate, and exchange information while working toward a shared goal.

Interaction usually involves:

- Structured messages (JSON, YAML, or protocol-specific formats)

- Task hand-offs where one agent passes output to another

- Requests and responses

- Shared memory updates

- Coordination logic such as “ask this agent next” or “retry this step”

It is also common to use well-known communication patterns such as:

- FIPA-ACL style messages, including fields like performative, sender, receiver, and content

- Contract-net protocol, where one agent announces a task, and others bid

- Auctions, where agents compete for tasks

- Voting or negotiation, when multiple agents must agree on a result

Multi-agent communication

Communication describes how agents talk to each other and how they organise their work. Structured messages ensure both the sender and receiver know precisely how to interpret the content.

Message formats

Agents commonly use standard, readable formats such as:

- JSON for structured fields, key-value pairs, status flags, and tool outputs

- YAML for lightweight configuration, metadata, or prompts

- Plain text when natural-language instructions are enough

- FIPA-ACL style messages when more formal semantics are needed.

FIPA_ACL defines a clear structure for agent messages, typically including fields like performative, sender, receiver, content, language, and ontology.

Transport channels

The actual communication may happen through:

- HTTP requests

- Message queues

- Pub/sub channels

- Direct in-framework function calls

Multi-agent coordination

Coordination determines who does what, in what order, and how the agent group makes decisions. It includes task allocation, negotiation, and conflict resolution when multiple agents attempt related tasks.

Contract-net protocol (CNP)

One agent advertises a task; other agents bid to handle it. The best-fit agent gets the task. It is useful when different agents have different capabilities or workloads.

The diagram below shows how CNP supports hierarchical organisational structures in which a manager delegates tasks to contractors, who further break them down into smaller subtasks and assign them to lower-level agents. In these cases, the manager can reasonably assume that contractors provide truthful proposals.

However, when agents have competing interests, the same protocol naturally evolves into a marketplace-style structure that closely resembles auction-based systems.

Auctions

Agents submit bids for a job based on cost, capability or priority. It is useful when multiple agents can perform tasks.

Voting or consensus

Multiple agents generate opinions or results and vote to settle on the most suitable output. It is quite useful in scenarios where agents need to perform evaluations or quality checks.

Negotiation

Agents negotiate roles, responsibilities, or data exchange when tasks require joint decision-making.

Multi-agent architectures

The architecture of a multi-agent setup defines how agents are organised, how they share responsibilities, and how decisions flow through the system. Choosing the right architecture is important as it affects scalability, reliability, and coordination overhead.

Keep in mind that the agents need to be built beforehand, and then the relevant architecture is selected to trigger the workflow.

Some of the most common architectures in MAS are:

Centralized architecture

One coordinator agent manages the entire flow and delegates tasks to other agents.

Example

For example, consider a long document with 50-100 pages as input, and the goal is to perform multiple tasks such as text extraction, clause identification, metadata extraction, summarisation, and compliance checks.

One central coordinator agent receives the document and assigns each task to specialized agents, along with input data, clear instructions, shared memory, and a list of tools necessary to achieve the goal.

- The extraction agent converts the PDF to text.

- The clause agent identifies important sections like payment terms and penalties.

- The summarisation agent composes a clean summary.

- The validation agent checks for missing signatures or required fields.

In the last step, the coordinator collects all individual agent outputs and prepares the final output for the user.

When to use

One downside of this architecture is that the coordinator agent always performs a final validation and it may skip some information or hallucinate due to the sheer volume of data. However, developers can create a manual human-in-the-loop verification script to prevent inaccuracies or information leaks.

Overall, centralized architectures work well when the workflow follows a fixed and predictable sequence.

Decentralized architecture

No single coordinator agent controls the entire workflow. Instead, each agent works independently while being aware of others responsibilities. Agents communicate directly with one another, exchange results as needed, and collectively complete the workflow through peer-to-peer interactions.

Example

Consider a use case in which an organisation receives thousands of emails every day, and each email needs to be classified, analysed, summarised, and routed to the right department.

In a decentralized MAS, the system follows a choreography-based model common in distributed systems. When a new email arrives, any agent can initiate the processing based on their role or capability.

- Classification agent reads the email and determines whether it is a complaint, inquiry, service request, or escalation. It stores this classification result in a shared memory or passes it directly to other agents.

- Extraction agent extracts important details such as customer name, ID, date, product number, or other sensitive information. If this agent needs to know the email category, it directly asks the classification agent.

- Summarisation agent summarizes the email. If this agent needs customer details, it requests them from the extraction agent. If it needs category information, it requests it from the classification agent.

- The routing agent looks at the summary, classification, and extracted details. Based on that, it decides which team, department, or service queue the email should go to.

All of this happens through direct agent-to-agent(A2A) communication. There is no central supervisor.

When to use

A decentralized system is useful when the system needs to scale, handle continuous inputs, or remain operational even when some agents slow down or fail.

The workflow continues even if one agent becomes slow (taking a long time, either while thinking or while completing the current task through extra steps) or encounters issues such as a JSON parsing issue or a model context length issue. Other agents can proceed with what they have, taking alternate paths. Since no single agent controls the sequence, the system has no single point of failure.

However, this architecture also requires careful design of communication rules, message formats, and error-handling. Developers must ensure that agents do not flood each other with requests or create loops. Proper logging, rate limiting, and shared memory discipline become important.

Hierarchical (nested) architecture

In a hierarchical setup, agents are arranged in multiple layers, much like an organisation with senior managers, team leads, and team members. Each layer has a specific responsibility:

- Upper layers focus on high-level decisions

- Mid-layers manage groups of tasks

- Lower layers handle detailed execution work.

This model is useful when the workflow naturally breaks down into stages, especially in unstructured data processing, where documents go through detection, extraction, cleaning, validation, and reporting.

Example

Consider a workflow where you want to process different types of unstructured documents, such as invoices, handwritten forms, and receipts. Each document requires several tasks, ranging from OCR to extraction to validation to the compilation of results. Hierarchical MAS divides the entire pipeline into clear layers, with each level supervising and coordinating the one below it. Here is how the workflow works:

When a new document arrives, a top-level agent (supervisor agent) first inspects the file and identifies what kind of document it is, for example, an invoice, a receipt, a handwritten form, or something else. This agent does not perform extraction or validation. Its simply determines which mid-level processing agent should handle this document and passes it along with basic metadata and context.

Once the document type is identified, a mid-layer processing manager takes over. For example, if the file is an invoice, the invoice-processing Manager Agent is responsible for managing the entire invoice pipeline. This mid-layer agent delegates tasks to lower-level specialists. The agent ensures that each step finishes successfully, handles retries when an error occurs, and maintains the state of the workflow before passing it to the next step or agent

Last layer agents do the actual, detailed work. An OCR Agent extracts text from images or scanned PDFs. A field extraction agent pulls out amounts, dates, and invoice numbers. A validation agent checks for format errors, missing fields, and incorrect totals.

After all stages are complete, a top-layer agent collects the processed outputs and compiles a final output in the requested output format mentioned in the prompt.

Coalition-based architecture

In coalition-based setups, agents form temporary teams depending on the task. When the task is done, the group dissolves, and agents return to an idle state.

Example

Consider a scenario where users upload mixed data: a PDF, an image of a receipt, or a voice note.

Instead of fixed pipelines, agents form a temporary coalition, starting with a temporary assessor agent that identifies the input and the ask. Temporary teams are formed, such as an OCR agent for images, a PDF agent for handling PDF documents, a speech-to-text agent that understands the query from a voice note, validation agents, and consolidation agents. Once the task is complete, the team dissolves, which makes it hard to reproduce.

When to use

Code generation tools use these architectures because the user usually provides the end goal, and the agents then automatically work to achieve the final output.

Workflow and orchestration frameworks for multi-agent systems

Once agents are defined, the next step is deciding how they should work together. This is where workflows and orchestration frameworks come in.

MAS workflow and orchestration frameworks help developers control the order of execution, pass data between agents, handle retries, and maintain context across multiple steps. They ensure that the multi-agent workflow runs deterministically rather than entering loops. Some popular frameworks, such as CrewAI, Langgraph, and FME, provide built-in support for these multi-agent architectures and workflows, also supporting features such as parallel execution, shared memory, and tool-based agents.

Creating a simple multi-agent system using FME by Safe

If you want to create a multi-agent system without any code, you can easily do so in FME by Safe, a no-code platform for creating structured agentic data pipelines. Here’s how you can use it to build the document processing agent discussed above.

Consider a contract document that needs to be processed and summarized by including two key pieces of information.

- Whether the contract is a supplier contract or a delivery vendor contract.

- Key clauses mentioned in the contract

Build this as a multi-agent system with a predefined workflow as shown in the image below.

Initialize a reader that reads the email content from a text file and directs it to the agents, as shown

Create a document classifier agent using an ‘OpenAIChatGPT’ connector. This example uses a simple prompt to classify the contract as a delivery or supplier contract based on the first paragraph of the input document.

Next, create a clause extractor agent using another ‘OpenAIChatGPT’ connector. A user prompt instructs the LLM to extract five clauses from the document.

Create a coordinator agent that combines both the inputs and produces a summary of the document. You can use a simple prompt to instruct LLM to combine both the information and create a summary. The completed multi-agent system looks as follows.

Implementing multi-agent systems is straightforward once you have a dedicated platform like FME with built-in LLM and vector database connectors, predefined flows, and transformers for data manipulation.

Challenges in building multi-agent systems

Building a multi-agent setup seems straightforward for small workflows, but real-world implementations come with several challenges. These challenges mostly arise because agents operate independently, generate their own intermediate outputs, use tools, and exchange information with one another. If not managed properly, the workflow can become nondeterministic or difficult to debug.

Some of the most common challenges while building MAS for domain-specific production environments are:

Complex coordination

As the number of agents increases, it becomes harder to manage who runs when, what data should be passed, and how to prevent conflicts. Without clear orchestration, agents may duplicate work, overwrite each other’s outputs, or get stuck waiting for missing inputs.

For example, two agents both attempt to extract metadata, producing conflicting values.

Communication overhead

Passing large messages (OCR text, logs, summaries) can slow down the MAS either due to long thinking time or large max token values. If communication is not well-engineered and structured, the workflow becomes inefficient and harder to monitor.

For example, an extraction agent unnecessarily sends a 20-page text block to multiple agents.

Emergent behaviours

In multi-agent workflows, agents often produce outcomes that were not intentionally programmed. This is known as emergent behaviour, and it can be both helpful and unpredictable.

Positive emergence occurs when agents naturally complement one another. For example, a generator agent produces a draft and an evaluator agent refines it, resulting in a better output than either could create alone.

Unpredictable emergence appears when one agent’s minor errors affect other agents in the system. For example, if an extraction agent mislabels a field and another agent depends on that value, the entire workflow may take an incorrect path.

Debugging is difficult

Tracking where a mistake occurred becomes challenging if multiple agents are modifying shared memory, calling tools, or changing context. You may need to manually intervene and pass the required distributed logs to the agent.

For example, finding out which agent hallucinated the missing field in a 5-agent workflow, where the mistake can be from the top level or at the last level.

Non-deterministic LLM outputs

Even with clear instructions, LLMs may generate slightly different responses each time. This inconsistency can cause branching decisions to change unexpectedly. This can be controlled by the temperature and seed parameters in OpenAI, but it is still prone to producing unexpected answers at any time.

For example, a classification agent gives “invoice” on one run and “financial document” on another.

Error handling and recovery

Agents can fail due to tool errors, API timeouts, or malformed outputs. The entire workflow breaks without fallback or try-catch methods.

For example, a tool-returned JSON fails to parse, and no fallback logic exists.

Best practices in building multi-agent systems

Some best practices to follow include:

Start simple and add complexity gradually, only if needed

Always start with a minimal, working configuration that includes two or three collaborating agents. Add more agents only when necessary. Suppose you are building a document-processing system. Start with just two agents: one for data extraction and one for summarisation. Once it is stable, add a third to include a validation agent that can verify whether all entities have been correctly extracted from the document. Later, add a user context agent to determine which context to pass to each document. This is how you can scale your architecture without compromising on accuracy.

Clearly define agent roles

Agents should have specific and narrow responsibilities. Avoid creating “general-purpose” agents tasked with multiple high-level tasks. Good practice is to develop task-specific agents with limited responsibilities.

Divide and conquer is one of the best techniques in MAS architecture. The current context always drives the language model’s next words. If we add more context or instructions to the language model, it may start responding to keywords in the context that are not relevant to its task.

Structure communication using JSON/YAML

When agents communicate with each other (or pass data), always use structured, machine-friendly formats such as JSON, YAML, XML, or standard agent-communication fields (e.g., per protocols like FIPA-ACL) rather than free-form, unstructured text.

Unstructured communication may lead to parsing difficulties, inconsistent interpretations, and unpredictable behaviour; structured formats ensure consistency, easier debugging, and validation.

Always use shared memory carefully

Shared memory (or a shared state store) can be very helpful in a multi-agent system, as agents can write and read common context, track progress, and share knowledge. But left unconstrained, shared memory becomes a source of chaos; agents might overwrite each other’s data or create an inconsistent state.

A good practice is to give read and write access only to a small set of agents. Isolate namespaces (for example: /extraction/, /validation/, /summary/), restrict write access to only these namespaces, and grant the rest read access.

It is also useful to define a Global State Schema in which each agent updates only specific parts of that state according to defined permissions. This pattern is common in graph-based agent frameworks like LangGraph, which manage persistent shared state across multiple agent nodes to coordinate workflows and memory.

Add logging at every step

Debugging a MAS is more challenging due to inter-agent communication, asynchronous behavior, and potential failures at multiple points. To manage this, it is essential to log every step, tag logs with timestamps, agent IDs, and message metadata, and make them searchable.

This helps trace where things went wrong, understand message flows, verify data integrity, and also helps when you decide to add monitoring, alerting, or audit trails. Logs and traces are also crucial for agents to track what has been done so far and what remains.

Some of the most common frameworks for logging and tracing MAS applications are OpenTelemetry, Structlog, Azure function logs, Application insights, LangSmith, LangFuse (open source), etc.

Provide fallback paths and retries

Since agents and language models are prone to encountering unexpected issues, it is generally good practice to include fallback methods for handling cases with multiple sequential steps. For example, in a document-processing multi agent system, if the OCR + Extraction Agent fails (due to poor scan quality), fall back to a simpler text-based extraction or flag the document for manual review; after N retries, escalate to a human-in-the-loop or logging + alert system.

Another example is when there is an error, such as an API key error or a context length error, and multiple agents encounter it. In this case, there should be a fallback manual function that can trigger a human in the loop or raise a try/catch exception and pass the exception to the user.

Use human-in-the-loop for final validation

Especially in regulated workflows such as finance or legal, a final human check reduces the likelihood of providing accurate or hallucinated answers. After all agent outputs are merged, a human reviews the result, understands the reasoning behind the wrong outputs and the expected output in the feedback, and then uses the feedback as a few-shot example.

Don’t over-use AI agents

It is not guaranteed that more agents lead to faster, more accurate results; it is recommended to always use custom functions with predefined inputs and outputs to gain more control over the architecture, making it more deterministic.

Last thoughts

As one explores multi-agent systems, one thing becomes clear: the real strength of these MAS lies not in the number of agents, but in how well they are designed to work together. Various architectural patterns offer different ways to bring structure to complex tasks that a single agent cannot manage alone. The real value comes from the way one defines roles, plans interactions, and shapes the overall workflow.

If one begins with simple designs, adds agents only when necessary, and keeps one’s workflows transparent, one can build systems that are easier to trust, maintain, and scale.

Frameworks like FME make implementing multi-agent systems easy with their drag-and-drop interfaces and built-in integration capabilities. FME is also great at data transformation and manipulation, especially in the spatial computing domain.

You can check out more details of FME here.

Continue reading this series

AI Agent Architecture: Tutorial & Examples

Learn the key components and architectural concepts behind AI agents, including LLMs, memory, functions, and routing, as well as best practices for implementation.

AI Agentic Workflows: Tutorial & Best Practices

Learn about the key design patterns for building AI agents and agentic workflows, and the best practices for building them using code-based frameworks and no-code platforms.

AI Agent Routing: Tutorial & Examples

Learn about the crucial role of AI agent routing in designing a scalable, extensible, and cost-effective AI system using various design patterns and best practices.

AI Agent Development: Tutorial & Best Practices

Learn about the development and significance of AI agents, using large language models to steer autonomous systems towards specific goals.

AI Agent Platform: Tutorial & Must-Have Features

Learn how AI agents, powered by LLMs, can perform tasks independently and how to choose the right platform for your needs.

AI Agent Use Cases

Learn the basics of implementing AI agents with agentic frameworks and how they revolutionize industries through autonomous decision-making and intelligent systems.

AI Agent Tools: Tutorial & Example

Learn about the capabilities and best practices for implementing tool-calling AI agents, including a Python-based LangGraph example and leveraging FME by Safe for no-code solutions.

AI Agent Examples

Learn about the core architecture and functionality of AI agents, including their key components and real-world examples, to understand how they can complete tasks autonomously.

No Code AI Agent Builder

Learn the benefits and limitations of no-code AI agent builders and how they democratize AI adoption for businesses, as well as the key components and features of these platforms.

Multi-Agent Systems: Implementation Best Practices

Learn about multi-agent systems and how they improve upon single-agent workflows in handling complex tasks with specialised roles, communication, coordination, and orchestration.