#FMECoin – What’s behind the map?

This is how it often happens. My colleague Robyn Jones knocks on the door in my office and asks: “Can we have a system in place that would track our #FMEcoin contest on Twitter in two days?”

I love this kind of challenge. The gears in my head start whirring: “We have TweetSearcher, which I’ve never used, so we can get the entries… somehow… Where do we keep the images? A chance to try our new DropboxConnector… How to show the data on the map? It’s really easy. I have almost too many choices — ArcGIS Online, CartoDB, Google Maps Engine (oh sorry no)… well, Google Fusion Tables lends itself best to the live map we need.”

“Yes,” I reply to my colleague. “We have all the pieces to make this happen.”

Of course, it took a bit longer than two days before the workflow was polished and fully automated, but two days were just enough to allow a smooth flow of submissions.

Component Overview

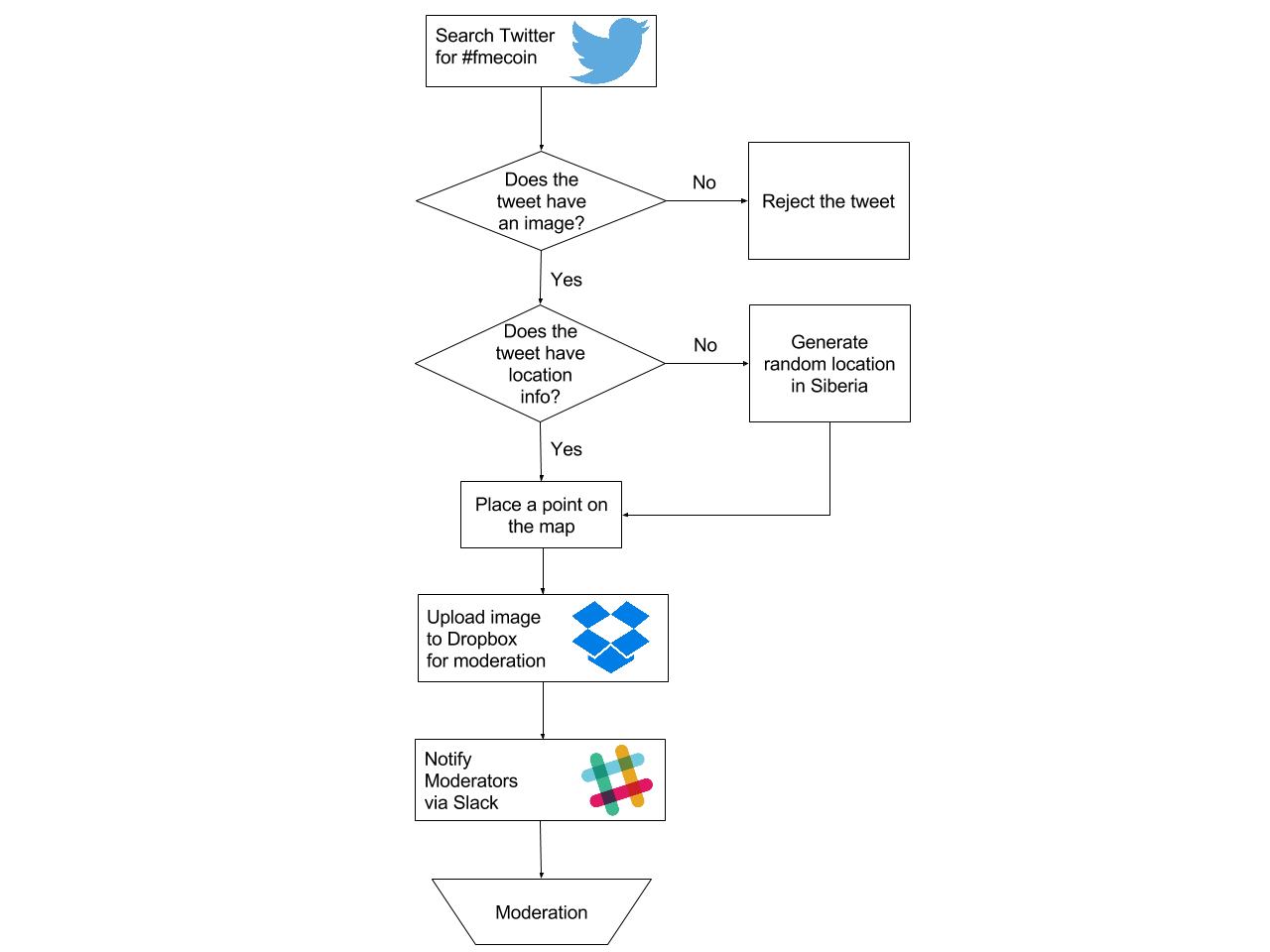

The workflow is split into two automated processes with a manual step in the middle. We scan Twitter for the #FMEcoin hashtag, and if a tweet has an image, we add a record to the PhotoSubmission Google Fusion table and download the image to Dropbox for moderation.

We introduced moderation in case some hypothetical entry contained something inappropriate. Once the system began to work we realized there were other, much more prosaic reasons for moderating and rejecting the entries — retweets, double entries, and images with no coins.

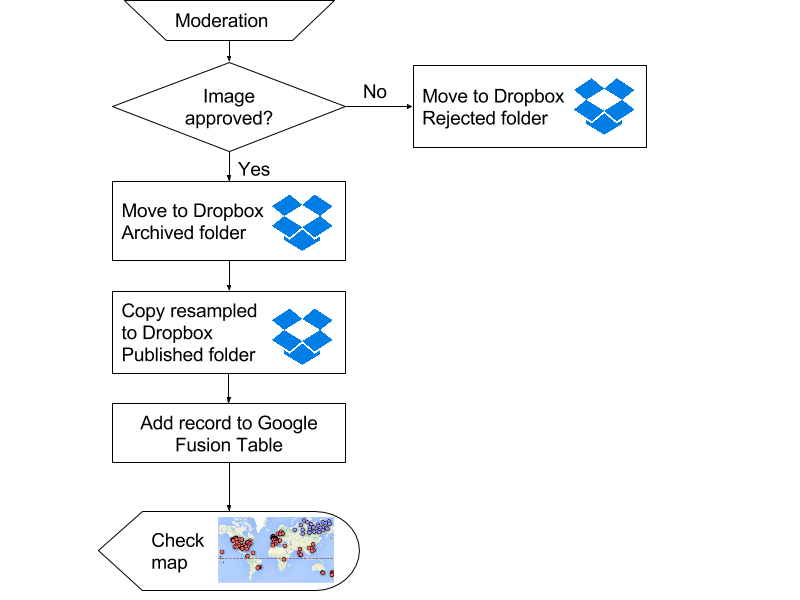

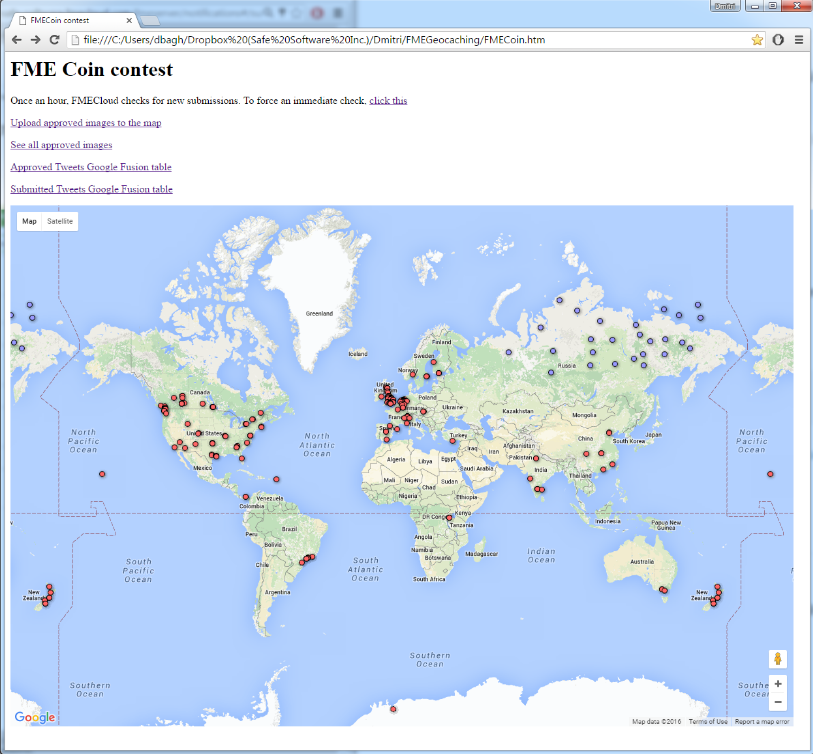

The second component publishes entries that passed moderation to the Photos Google Fusion table. This table, in a map mode, is what you see on our Contest Page.

An extra workspace can read the approved photos table and show all entries on a single page.

All three workspaces created for the contest are published to FME Cloud, and run depending on different triggers — schedule, Dropbox event monitoring, and a click on a link from the contest page.

Interesting technical details

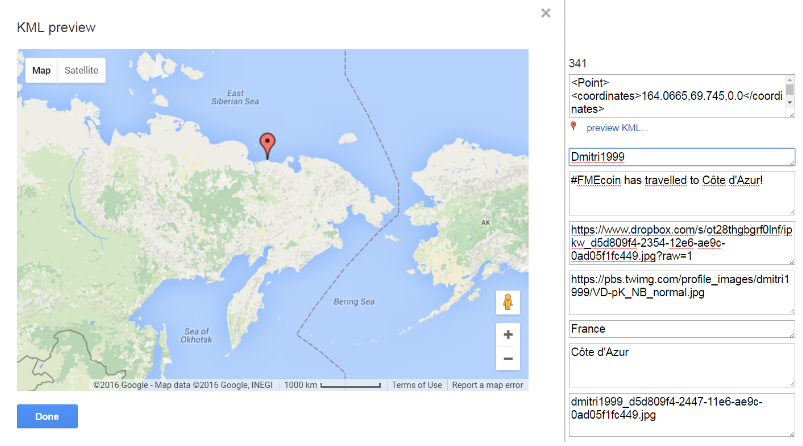

Twitter API response

TweetSearcher outputs one feature per each tweet found. It has a few attributes such as _tweet_id, _tweet_user, _tweet_text, _tweet_date, and a piece of JSON text, which contains everything mentioned above and a lot more. We try to extract coordinates from the “geo” section:

geo":{"type":"Point","coordinates":[51.1322187,-114.0114326]}

and failing that, from the “place” section:

"place":{"id":"07d9ca7292c86001","url":"https://api.twitter.com/1.1/geo/id/07

d9ca7292c86001.json","place_type":"poi","name":"Gate D46","full_name":"Gate

D46","country_code":"CA","country":"Canada","contained_within":[],"bounding_

box":{"type":"Polygon","coordinates":[[[-114.014815700015,51.1328892697298],

[-114.014815700015,51.1328892697298],[-114.014815700015,51.1328892697298],

[-114.014815700015,51.1328892697298]]]}

Among other values, we extract the url of the profile image, the country, and the place name.

Finding only new tweets

We can limit how many tweets we get from TweetSearcher, but we really need just the new tweets, those that were submitted after the last run of the submission workspace. Each tweet gets a unique ID assigned by Twitter. This number is always growing, so tweets published later have higher IDs. For tracking the highest Tweet ID in each run, I created a simple text file, which stores this number. But where should I keep it? If I make it local, only I will be able to run the workspaces, and they won’t work in an FME Server environment, where this workspace should reside while the contest runs. It will be really easy for anyone in our great Server team to make such a workflow, but I am not very experienced with FME Server. How can I get the best of both worlds — the convenience of the file system on the local machine and all the power of the server and web? Dropbox is the answer. In FME, it is implemented through the DropboxConnector transformer. When we upload a file to Dropbox, it gets a normal https:// address. At the same time, this file lives on my computer on a C: drive, I can easily open and change it, which is really handy during the testing phase of the project.

So now, when the workspace runs, it reads the highest Tweet ID from Dropbox set in the last run, searches for all the recent tweets with #FMEcoin hashtag, extracts their Tweet IDs, finds the highest number among them, and updates the ID file in Dropbox. Tester compares the highest Tweet ID from the last run with current IDs and passes only tweets with higher numbers for processing.

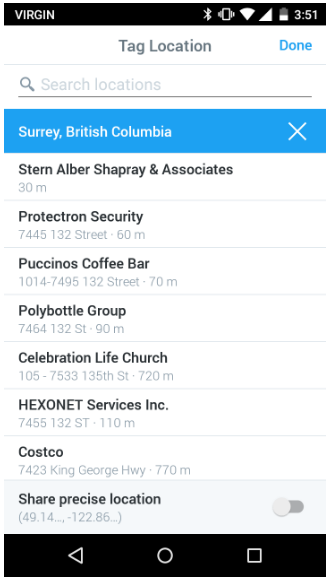

Tweet location

To my embarrassment, it took me a while before I figured out how to correctly specify location in a tweet. I incorrectly assumed Twitter would use the coordinates from the images I submit — as a geographer, I always keep location functionality turned on in my devices.

No, with Twitter, I either can choose a named location from the list, or switch to sharing my precise location taken with GPS.

To my relief, a lot of people made the same mistake. Maybe, our advanced geographical awareness played a role in this systematic error, or maybe the location functionality is an unfamiliar feature to many Twitter users.

After some debates we decided to place the tweets with no location into Siberia. This generated a lot of jokes about coin repatriation adventures and misled tourists.

If I find the right location of the tweet based on its text or can get the coordinates directly from the users, I manually move the coins where they belong.

Dealing with images

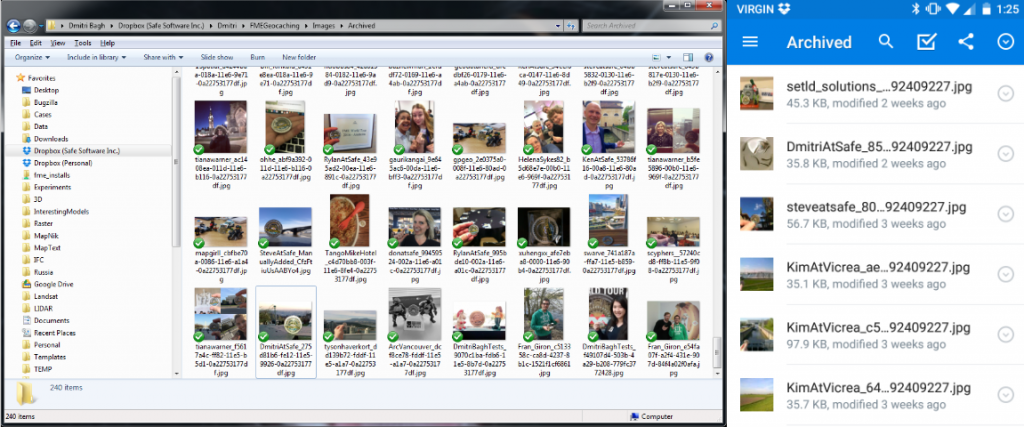

After the success with Tweet ID, I didn’t hesitate to use Dropbox for storing images from the tweets. The body of the Twitter response has a link to the image, which I get with ImageFetcher, and, without saving to my local drive, I immediately upload it to Dropbox, which will take care of the rest — the image will be addressable via https protocol:

https://www.dropbox.com/s/e7v4s5ij2cpuw9m/DmitriAtSafe_275d81b6-fe12-11e5-9926-0a22753177df.jpg?raw=1

It also will live on my desktop. And my laptop. And my iPad. And even my Android phone.

From the submissions folder we manually move files to either “Approved” or “Rejected” folders. The files moved to “Rejected” folder are retired, we don’t touch them anymore.

The files from “Approved” folder automatically go to “Archived” folder and the downsized versions are placed into “Published” folder. These are the images that we use on the map and on the report page. DropboxConnector lists all new submissions, copies files to new folders, and deletes the processed files. In this workflow, DropboxConnector is our main tool for physical manipulations with the files.

Dropbox vs. Amazon S3

Maybe, the last thing worth mentioning in this section — Dropbox is a very convenient tool for storing and sharing files between computers and users. It is not that great for fast delivery of web content — if I would need to put this workflow into a real production cycle, I probably would go for Amazon S3 storage, for which we have a family of four S3 transformers with the same functionality as a single DropboxConnector (we definitely need some unification here).

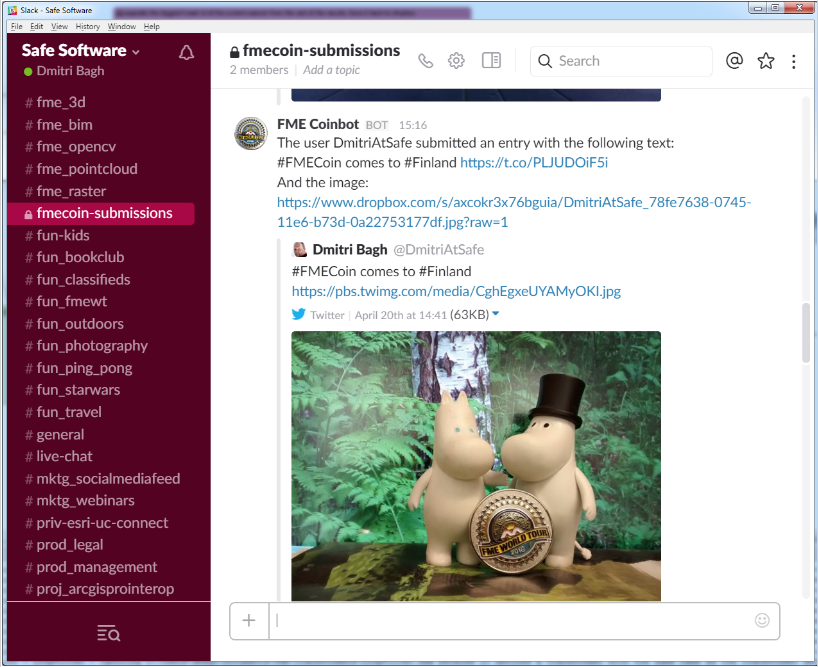

Slack notifications

A few years ago I wouldn’t have any doubts — an email is the best notification service. But when Slack was introduced for internal office communications, our use of regular emails dropped significantly. At this moment, I have only 6 internal messages, three of them are from the bots, among the last 50 emails — the rest comes from the outside world. I created an FME Coinbot that delivers messages to the Slack coin submission channel.

A few years ago I wouldn’t have any doubts — an email is the best notification service. But when Slack was introduced for internal office communications, our use of regular emails dropped significantly. At this moment, I have only 6 internal messages, three of them are from the bots, among the last 50 emails — the rest comes from the outside world. I created an FME Coinbot that delivers messages to the Slack coin submission channel.

The bot posts the text of the tweet and shows the image that comes with the tweet:

For us, it is a signal to go and make a decision whether to approve or reject the submission.

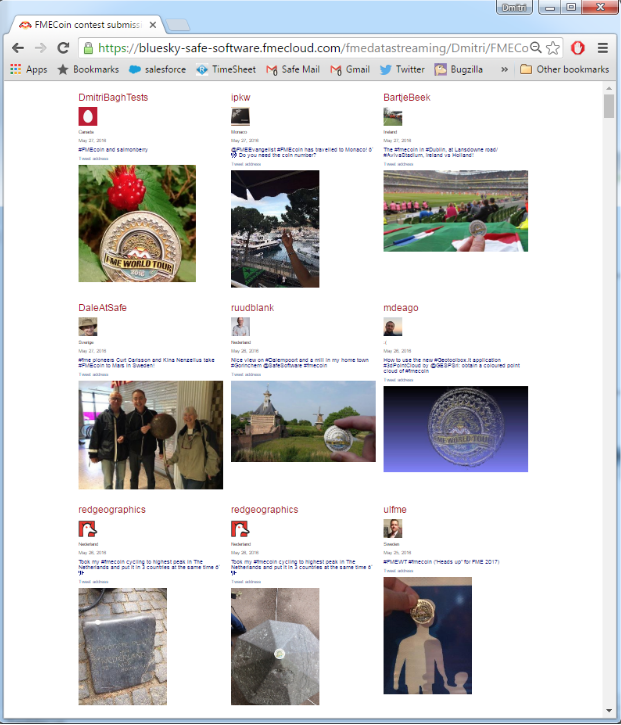

Picture gallery

A workspace for generating picture gallery uses two HTML transformers. HTMLReportGenerator creates multiple small HTML attributes, which, if we would save them as *.html file, will make nicely formatted web pages. HTMLLayouter combines them into a grid.

This page is dynamic — in fact, it is a workspace hosted on FME Cloud that stream the freshest contents of our approved submissions database into your browser, grabbing images from my Dropbox and Twitter profile image repository.

Automation: Enter FME Server

To automate this workflow, I uploaded all three workspaces to FME Cloud and set some rules for executing them. The submissions are checked once an hour. Now when the 16th minute of every hour approaches, I eagerly anticipate to see where else our users take their coins.

After receiving a notification, my colleague Robyn or I check the submissions and move them either to Approved or Rejected folders.

The Approved folder is under constant monitoring by DropboxWatch, a protocol that reports changes in Dropbox folders to FME Server.

I also created a subscription for this publication, which runs every time the Approved folder receives a new entry. The subscription runs the second workspace that moves the approved images to Archived and Published Dropbox folder and inserts a record into Approved Google Fusion table.

Finally, the Gallery workspace runs on demand — that is, whenever someone presses the workspace link:

https://www.dropbox.com/s/r6gg9me8o3gc04q/report.htm?raw=1

Management console

For our internal use, I made a simple HTML page with all the important links and the embedded map:

Conclusions

When I came to Safe Software 11+ years ago, I mostly worked with vector and tabular data. Then we added rasters, point clouds, BIM, web services — our data type diagram is always growing. The times when FME was only a product for moving data between CAD and GIS are in the past.

The FME Coin contest shows how FME Desktop integrates several web services into a single workflow, allowing data to travel seamlessly between different destinations and get published very easily. Throughout the entire workflow, FME never actually reads or writes a file that lives only a single location on disk. The data is always in the network somewhere. The file is dead. Long live the file!

The workflow involves five different online services — Twitter, Dropbox, Slack, Google Fusion Tables, and Google Maps. The spatial data is generated from JSON responses and stored as KML geometry, rasters travel from Twitter repositories to Dropbox folders, the results are visualized directly in browsers and available to anyone in the world.

FME Server is a very powerful, very friendly product — I was able to make all the FME Server steps by myself, only once asking for help with Dropbox integration, where I made a trivial error.

I would really love to design a few more such contests. And we even have a few ideas in mind, so stay tuned for more!