Norway Minecraft Project Paves the Way to Open Data in the Cloud

What started out as a fun project in support of kids at an annual Hackathon event quickly turned into a real-world test bed for an upcoming cloud-based open data portal rollout – and changed the way they work.

What started out as a fun project in support of kids at an annual Hackathon event quickly turned into a real-world test bed for an upcoming cloud-based open data portal rollout – and changed the way they work.

As an unabashed geonerd, I’ve greatly enjoyed writing about the emergence of spatial-to-Minecraft projects over the last few years. I’ll admit that the “what’s it good for?” of it was a bit of a head scratcher at first, though the coolness factor was never in question.

Public outreach, education, and youth engagement have been prominent themes so far. And when two of my favorite early spatial-to-Minecrafters got their heads together recently, what emerged covered not only those topics, but an actual business case too.

To be more exact, what started out as a feel-good project with a focus on kids turned into a real-world reusable test bed for Kartverket’s (the Norwegian National Mapping Agency) upcoming rollout of a cloud-based Open Data portal.

And it all started with a Hackathon.

You know, for kids! *

This annual event, hosted this year by Kartverket at their location in Hønefoss, also has a junior division for youth.

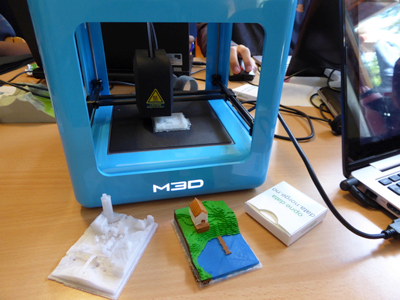

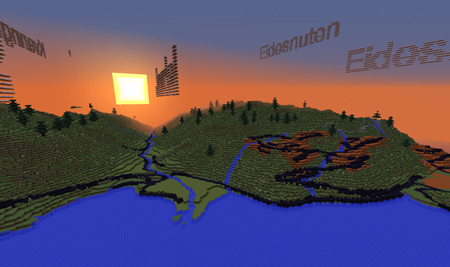

Boele Kuipers, Technology Coordinator at the mapping agency had been collaborating with Safe partners Sweco to build an FME Cloud-based LiDAR data delivery prototype, and they decided to take the same concept and build an on-demand Minecraft world provider for the Hackathon. The entire country of Norway would available, and the kids could simply request the area they wanted.

It was a fun idea, but it wasn’t long before they realized that the amount of processing and capacity would be pretty similar to, say, the national distribution of a terrain model or any number of spatial datasets. They would be able to build this system, have a real-life (but non-critical) test of it, and repurpose almost all of the work to deliver “official” data to the public.

And so they did!

“The kids understood the interface right away,” says Boele. “They all headed pretty much straight for their hometowns. Standing in the back of the room, watching 50 kids work and play in their homeworlds, well, I was pretty proud! Some of them even had projects going over to Blender. It was amazing to see 12-year-olds doing highly professional work in a 3D modeling environment.”

The System

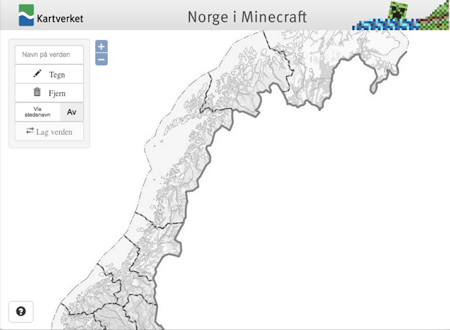

Ulf Månsson and Peter Segerstedt at Sweco were instrumental in assisting putting the system together. With access to web developers, creating the front-end was quick and easy to do, giving the user simple tools to define an area of interest to create and prepare for download.

The source data, which is not pre-processed into Minecraft format, is sitting in the cloud on Amazon, and includes terrain and various supporting datasets in PostGIS. FME Cloud handles the workflows.

“If you know FME and FME Server, doing something like this is easy,” says Ulf. “There’s a lot of data to process, but the work is mostly just thinking through the workflows. Setting them up in the cloud is simple.”

Who knew it would be this popular?

The Minecraft service was kept under wraps until after the Hackathon, when it was released publicly. The media picked up on it, and the traffic exploded. The site had been providing a few hundred downloads every other day. But when the article came out, within just minutes there were thousands of hits.

At peak traffic, they generated 4,000 worlds in an hour.

And though the traffic has settled back down to more manageable levels, the team now knows what it takes in terms of support and burst capacity to keep things performing.

And so, as a trial run for “real” data, the project was an unqualified success.

“The Cloud is changing the way we work.”

According to Boele and Ulf, this project was carried out unlike anything they’d worked on previously, and they enjoyed it immensely.

“It was a joy to work on,” says Boele. “We could just find our way along with size and capacity, without having to preplan hardware and resources. It was a bit improvisational, which was great. The cloud structure meant we could come up with a change or new approach and change it instantly to see how it worked.”

“It was a joy to work on,” says Boele. “We could just find our way along with size and capacity, without having to preplan hardware and resources. It was a bit improvisational, which was great. The cloud structure meant we could come up with a change or new approach and change it instantly to see how it worked.”

“That process is very much possible because of FME Cloud,” adds Ulf. “Imagine installing FME Servers, getting firewalls up, getting data across – and then wanting to change something. You can’t react and prototype the same way. It’s a new way of thinking, and it’s changing the way we work. Now we want everything in the cloud!”

Now that they have the Minecraft experience and the benchmarks it provided, they can move on to re-purpose what they’ve done for official data, already comfortable knowing how it should perform.

You can download your own piece of Norway on their website.

* I haven’t been able to get Tim Robbins pitching the hula hoop in The Hudsucker Proxy out of my mind the entire duration of working on this article and thinking back to “Minecraft? Yeah, but what’s it good for?” So here’s a clip. You know, for kids!

And here are some actual resources, if you’d like to learn more!

Recorded Webinars: